Can a Squash Cross with a Melon? And Other Cucurbit Questions

The family Cucurbitaceae is such an important plant family for food production. From this family come many of the annual veggies we know, love, and rely on to fill our pantries and our bellies. It gives us cucumbers, melons, watermelons, summer squash, winter squash, and pumpkins.

Many kinds of curcurbits are not edible for humans, but we have learned to cultivate eight edible species in this family. I want to take a look at the six most commonly grown species, so that we can understand the food we’re growing and become more successful gardeners.

But first, we need to unpack a crucial concept that every gardener needs to understand: cross-pollination.

What Makes a Species, and Why Do Gardeners Need to Understand it?

The common saying goes, “Knowledge is power.” I would argue that in the garden, knowledge is empowerment. When we understand how plants germinate, grow, live, and reproduce, we can better meet their needs and get consistent yields of produce. When we know how botanical processes work, we can dispel myths and create more productive gardens.

So let’s empower ourselves when it comes to the whole host of myths that swirl around cucurbits this time of year. And let’s begin with looking at how plants reproduce.

A biological species is a group of organisms that can reproduce with one another in nature and produce fertile offspring.

Species are characterized by the fact that they are reproductively isolated from other groups, which means that the organisms in one species are incapable of reproducing with organisms in another species.

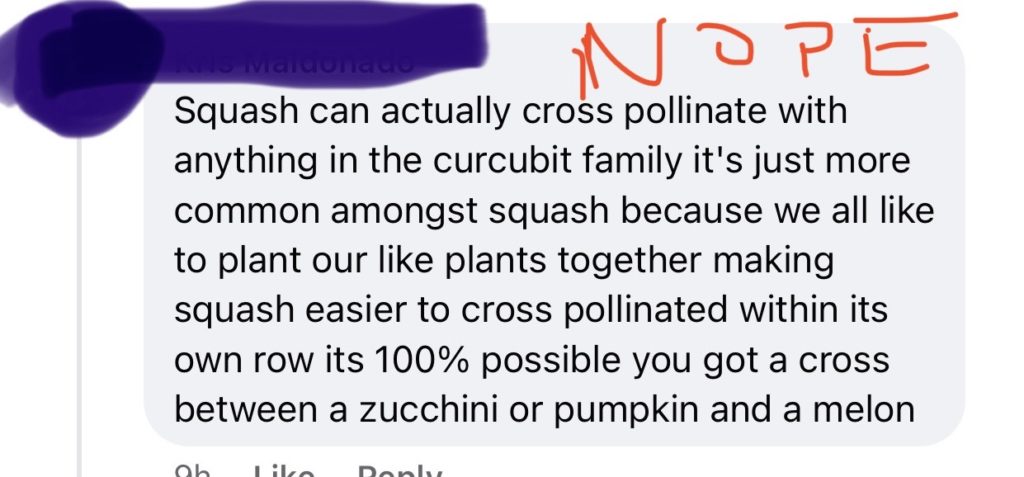

Species in the same family (such as the Cucurbitaceae family) are related to each other, but one species in the cucurbit family cannot cross-pollinate and create viable seeds with a separate distinct species in the same family.

Cross-Pollination…It Only Happens in Species

So, if only plants within a species can produce viable offspring with each other, what is cross-pollination?

Essentially, the melon you are picking this year is the swollen, mature ovum of the melon plant you planted out in the spring. The seeds inside that melon are the potential offspring that, if grown under the right conditions, will produce new melon plants next year. A melon is part of the parent plant, and it will express the genetics of the plant. (Much like a woman’s uterus contains her DNA and is part of her body, the melon is a part of the parent plant. It will not contain genetics from the male. )

This means that cross-pollination will not impact this year’s fruit, should it occur. If you grow a Spaghetti squash next to a Black Beauty zucchini (both C. pepo.) , you can count on the fact that the spaghetti vine will produce spaghetti squash, because it is the mature ovum of that plant. Same for the zuke. Only the seeds contain a mix of genetics from the male and female plant.

Let me reiterate, because this myth gets perpetuated over and over in gardening groups: if you grow one variety near another, or one cucurbit species near another, it will not mess up the fruit this year.

A Brief Look at the Cultivated Cucurbits

Summer/Winter Squash Species

Cucurbita pepo – A species of cucurbit that has been cultivated for thousands of years. Both vining and bush growth habits exist, with more male flowers being produced early in the life of the plant, and females coming along later. Commonly grown varieties include Acorn and Spaghetti. This species also includes the traditional “pumpkin” we carve into Jack-O-Lanterns at Halloween.

Summer squash also come from this species. Zucchini including traditional varieties such as Black Beauty, Cocozelle, and the round Eight Ball (perfect for stuffing and baking) are all C. pepo. Other favorites include Pattypan and Yellow Crookneck.

Cucurbita moschata – You may have heard that Butternut squash always come true from seed. This is one cucurbit myth that has a large element of truth to it. Butternut is the only C. moschata grown in most North American gardens. This means that it does usually come true from seed, because it cannot cross with the two other common species of garden squash. However, as interest in growing winter squash grows, more varieties from this species are becoming readily available, including Seminole, and Calabaza.

This species is more resistant to squash vine borers and disease and does well in hotter climates.

Cucurbita maxima – If I had to pick one species of annual veggie I could not do without, it is this one. It is a staple of our diet, enjoyed roasted, in baked goods, in soups and stews. Dozens of excellent varieties exist, including the superb Burgess Buttercup (pictured above), which is an excellent keeper squash with superior flavor and texture.

My other favorite is Angela’s Sweet Meat (I’ve been saving my own seeds from an original packet of Sweet Meat for so many years, the squash is adapted to my microclimate) which can keep for 9 months or more under my kitchen table.. Other varieties I grow consistently include Black Futsu, Red Kuri, Blue Hubbard, and Jarrhadale. Giant pumpkins grown for competition are also in this species.

C. maxima is a vigorous vining plant, and fits best in a smaller garden when grown up a trellis, and larger fruits should be supported by slings as they mature.

(Note: due to its more hardy and pest-and disease resistant nature, in the mid-20th century, work was done to create an interspecific cross (F1 hybrid) between C. moschata and the more productive C. maxima. The resulting squash, Tetsukabuto, has the expected hybrid vigor, produces large yields, and is more pest- and disease-resistant than C. maxima.

You will not be able to reproduce this on your own by accident in your garden. Tesukabuto squash are interspecific hybrids, do not produce viable seed, and are not even able to pollinate themselves. You must grow the appropriate varieties near them to get fruit. And the fruit must be cured at least 6 weeks before eating. You can purchase the seeds here.)

Cucumber

Cucumis sativus – Much like apples, which can be divided into cider, dessert, and baking, cucumbers can be divided into three groups: pickling, slicing, and burpless. (Note that cucumbers are not even in the same genus as squash. They are that much more distantly related.)

Pickling: Boston Pickling (I consider this my favorite variety for making lacto-fermented dill pickles due to the size and thin skin), Eureka, and Northern Pickling.

Slicing: Lemon (pictured above, produces very well in mild summers. Bright and lemony in flavor, it’s delightful in salads), Picolino (a crisp cocktail cuke), and Marketmore/Marketmore76, which produces well in shorter seasons.

Burpless – This class of cucumbers has thinner skin. Since the skin contains cucurbitacin -a compound which can cause GI issues in some folks – thinner skinned varieties are considered “burpless”. They are also often seedless. (In very large quantities in wild cucurbits, it is this same compound which makes cucurbits toxic. It is the dose that makes the poison, afterall.) Varieties include: Tendergreen Burpless, Muncher, and Burpless No. 26.

My favorite way to enjoy cucumbers is in tzatziki (you can find my recipe in a vintage post here).

Melons

Cucumus melo – This species are the true melons (their origin is still debated: India? Africa? East Asia?). Most are egg-shaped or round, including the cantaloupes, honeydews, and crenshaws. But you won’t find watermelons here.

My gardening relationship with melons is nothing short of compliated. My culinary relationship with them is simple: I have yet to meet a melon I don’t enjoy eating. This close relative of the cucmber boast a hugely diverse group of fruits whose complex sweet flavor, musky aroma, and succulently juicy flesh are enjoyed in hot climates around the world. Unfortunately, I don’t live in one of those hot climates.

Melons prefer long, hot seasons, and while the garden season in Western Oregon is long, the hot months are short (and sometimes non-existant). Can I grown cantaloupes? Yes. Can I get them to mature enough to produce the appropriate sugars and flavor profile? Most years, no. I sure can get a lot of 2/3 sized melons that taste like cucumbers, though.

Years ago when I had half as many kids as I do now, I had the energy to grow them over black plastic to heat the soil, reflective pans to add even more heat, and baby them into producing a good crop for me. Now, if I bother with melons, I stick to petite varieties that will give me the sweet dessert-worthy fruits I crave: Minnesota Midget, Honey Bun, and Sleeping Beauty.

If I had my druthers and knew the summer was going to be warm, I would grow Charentais every year, though. It’s definitely a winner – even for folks who don’t like the musky flavor of many melons.

Citrullus lanatus – Unlike many of the cucurbits we know and enjoy, watermelons originated in Africa, not South and Central America. They are in a different genus than other cultivated melons, and cannot cross with them.

As you might imagine based on their origin, watermelons like hot weather. Again, not an ideal crop for Western Oregon. If you’re going to grow them in cooler climates, stick to varieties specifically bred for such locations. I have successfully grown Cream of Saskatchewan in my garden, for example. Other varieties have joined the “it’s now September and I guess this melon is never going to ripen past ‘mature enough to pickle but no sugars develop’ stage.” pile with larger musk melons and cantaloupes.

Growing Cucurbits with Confidence

Cucurbits and the garden mythology surrounding them can be confusing. The more we learn about the lineage and complexity of our garden veggies, the more fascinating they become. The more we learn about the way plants interact with each other, function, and reproduce, the more empowered we become as growers of our own food.

Here are the two big takeaways I hope folks can glean from this article:

- There’s no need to worry: you can grow different species of cucurbits near each other and get the expected harvest you planted for: Melon plants will produce melons, squash plants will produce squash, cucumber plants will produce cukes.

- If you save seeds from on species of cucurbit you can be confident that it won’t make a canta-squash or a cuke-zuke. If you want to save seeds from one variety, make sure it is hand-pollinated only with that variety, and it will come true from seed next year. (If you don’t want to bother with hand-pollinating, simply grow only one variety of each species.)

For a more detailed dive into our cucurbits, including the concepts of toxic squash and mutt pumpkins: